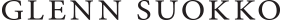

The Andy Warhol Interview Session, 1985

In my first position as an art director for a magazine publisher, I interviewed Andy Warhol while he created a digital self-portrait on an Amiga computer — perhaps the first of its kind by a major, working artist.

Many people claim to have known or met Warhol. I count myself among them, though my brief encounter with him may ultimately be a small, newly positioned question mark in art history. I was twenty-five years old, in my first professional role, when I met Warhol in New York and later interviewed him at his studio, The Factory. During that session, I sat beside him as he worked, guiding him a bit through a software program as he produced what may be the earliest known computer-generated self-portrait by a major artist.

A single print was made from that digital file and remains the only extant artifact; to my knowledge, the original digital file no longer exists. Over the years, I’ve been asked often about that interview and the image he created during our meeting.

In 1985, before our interview, Commodore International had given Warhol a newly released Amiga computer to experiment with using a graphics program called ProPaint. On July 23 of that year, at Lincoln Center in New York, he gave a live demonstration during the launch of Amiga World magazine, “painting” on an Amiga a video-based image of Debbie Harry from Blondie. I was in the audience that evening, serving as art director for the magazine. A few months later, the editor-in-chief, Guy Wright, and I met Warhol at The Factory to conduct an interview while he created a digital self-portrait, which became the cover image for a special issue of the magazine.

After Warhol completed the image, I located one of the few labs in Cambridge, Massachusetts capable of taking a floppy disk and producing a high-quality print from the file — this was before the era of desktop publishing and integrated page-design software. That print became the magazine’s cover artwork. I kept it as a personal memento of what was, for me, a pivotal experience, and it remains in excellent condition today.

Warhol’s self-portrait shows him seated before the Amiga, holding a computer mouse, his image repeating infinitely on the computer screen like a hall of mirrors. The concept is loaded with meaning: time and infinity, looking back and forward, the artist both inside and outside the machine — the tool and the canvas merged. The visible pixels remind us of the early days of digital imagery, when each square of color could be counted with the eye.

At the time, the idea of using a computer for serious creative work was widely debated, echoing the 19th-century skepticism toward photography as an art form. The interview and image were published in Amiga World in January 1986. For years afterward, curators, collectors, and critics dismissed Warhol’s computer-based work as commercial, created under contract with Commodore, and therefore not “true art.” That view is now shifting.

Warhol died in 1987, but renewed interest has emerged around his Amiga experiments. In 2021, Christie’s, in collaboration with the Warhol Foundation, sold five NFTs based on rediscovered digital images Warhol made on the Amiga in 1985 for $3.38 million. In 2024, Artnet and Art Now LA reported that materials compiled by a Commodore technician who attended both the Amiga launch and our interview are being offered for $26 million. Other media outlets have since revisited the story, extending the conversation into the digital age.

I find it fascinating to watch how this narrative evolves — how history reframes what was once considered trivial. The questions raised in 1985 about creativity and technology echo today’s debates about artificial intelligence, authorship, and originality. Warhol’s experiment on the Amiga stands as an early marker in that dialogue, linking art and technology in ways we are only beginning to understand.

One print, made directly from the original digital file, remains. Warhol valued prints and spoke about their significance during our interview. What began as a commercial assignment for a magazine may also represent an important intersection of creative and technological history — a point where traditional art met the emerging digital frontier. Whether it becomes a lasting benchmark or simply a small footnote in art history remains to be seen.

August 2024

Top: Andy Warhol and Glenn Suokko, The Factory, New York, 1985.

Middle: The portrait, 1985, original print from the ProPaint digital file, 18¼ x 14¾ inches.

Left: The cover of Amiga World magazine, 1986, design by Glenn Suokko.